In this lecture note, we will review the fundamental concepts of cryptography that are essential for understanding modern security systems. We’ll cover encryption methods, hashing, key exchange protocols, digital signatures, and how these concepts work together to secure communications in real-world applications like HTTPS, SSH, and cloud services.

Encryption

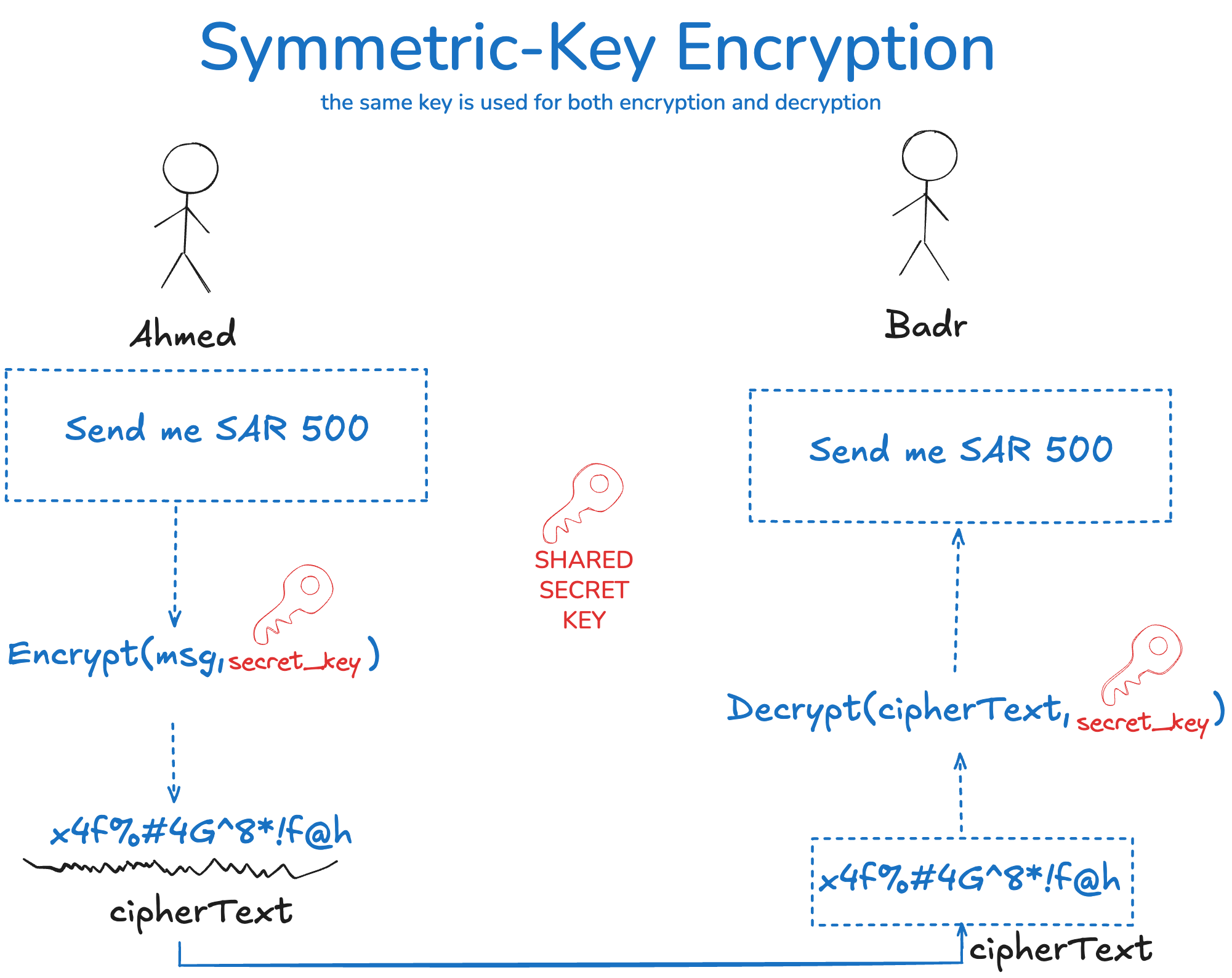

Symmetric Encryption (also known as Private Key Encryption)

Symmetric encryption uses the same secret key for both encryption and decryption.

- Key Sharing: The sender and the receiver must have the same secret key.

- Confidentiality: Only the person with the secret key can read the message.

- Performance: Computationally efficient, uses less power, and encrypts/decrypts data quickly.

- Use Cases: Ideal for encrypting large amounts of data, streaming data, and scenarios where speed is critical.

- Key Distribution Problem: The key exchange is difficult. It must be securely shared between sender and receiver.

- If the secret key is intercepted by a third party, confidentiality is compromised.

- Can’t be used alone, we need

- Authentication Problem (repudiation): We can’t verify the sender’s identity and tell for sure who sent the message.

- We only know that the message was encrypted or decrypted by someone who has the secret key, but either party could later deny (repudiation).

- Symmetric encryption alone cannot securely exchange keys or provide authentication.

- It is typically used together with asymmetric encryption, where asymmetric algorithms handle both key distribution and authentication, and symmetric encryption handles fast data encryption.

Which Key Is Used for Encryption and Decryption?

The same key is used for both encryption and decryption.

Common Symmetric Encryption Algorithms

- Advanced Encryption Standard (AES): Uses 128-, 192-, or 256-bit key lengths. Modern, secure, and the most widely used symmetric encryption standard today.

- Data Encryption Standard (DES): Uses a short 56-bit key. Now considered insecure due to vulnerability to brute-force attacks; deprecated and no longer used.

- Triple DES (3DES): An improved version of DES that applies DES three times using multiple keys. More secure than DES but slow and being phased out in favor of AES.

- Twofish: A fast, flexible, and secure symmetric cipher that uses 128-, 192-, or 256-bit key lengths.

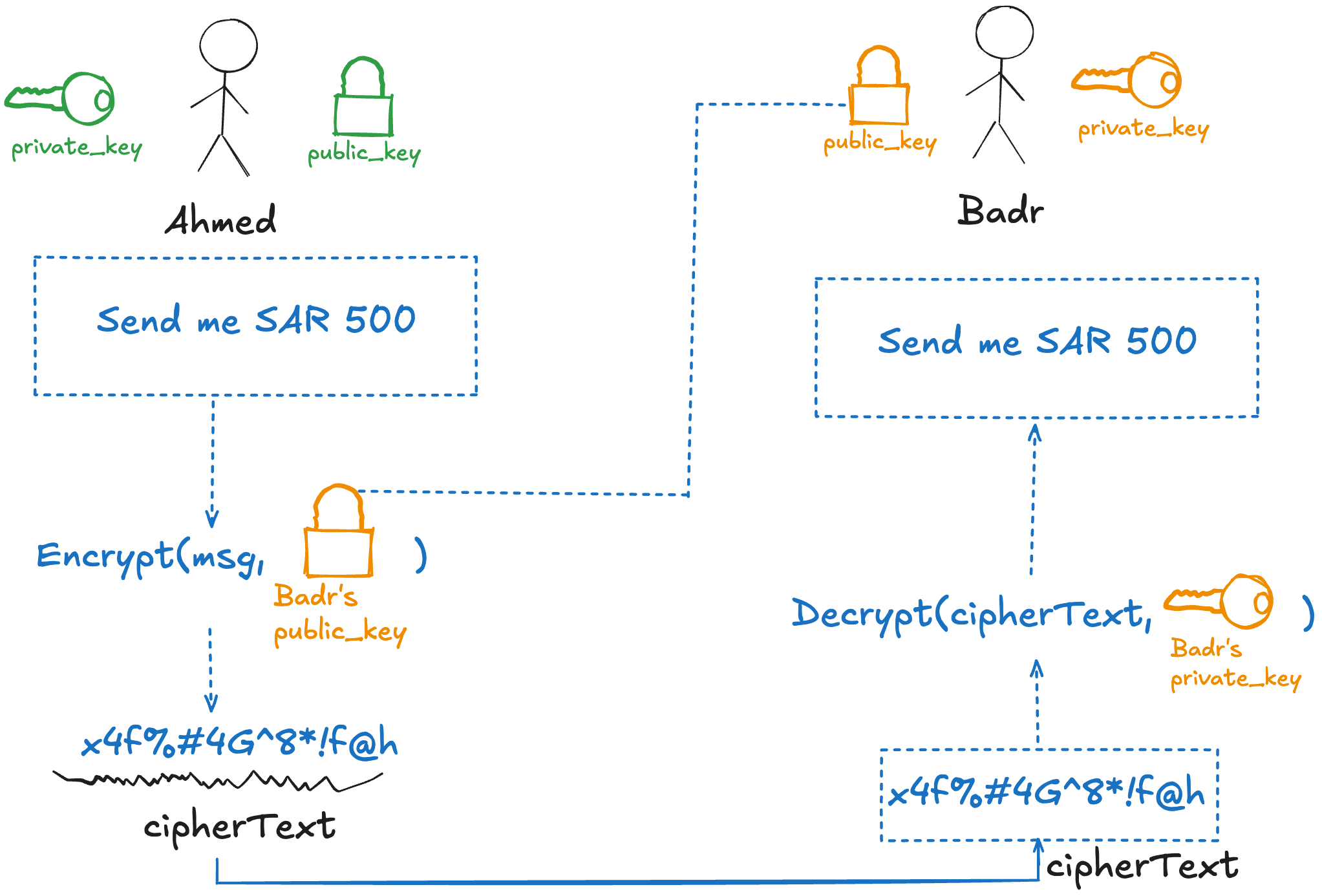

Asymmetric Encryption (also known as Public Key Encryption)

Asymmetric encryption uses a pair of keys: a public key (shared openly) and a private key (kept secret). Data encrypted with one key can only be decrypted by the other key.

- Confidentiality: Messages encrypted with the recipient’s public key can only be decrypted by their private key.

- Key Distribution: Solves the key distribution problem because the public key can be shared freely without compromising security.

- Performance: Computationally heavier and slower than symmetric encryption, but solves the key exchange problem and provides authentication.

- Authentication and Non-Repudiation: Digital signatures created using the sender’s private key can verify the sender’s identity and prevent repudiation.

- Use Cases: Key exchange, digital signatures, establishing secure connections (e.g., SSH, TLS/HTTPS), and scenarios requiring authentication or non-repudiation.

Which Key Is Used for Encryption and Decryption?

It depends on the purpose of encryption: Confidentiality (Encryption) or Authentication and Non-Repudiation (Digital Signature).

Asymmetric Algorithms for Confidentiality/Encryption

- If the goal is to encrypt the message and provide confidentiality, so others can’t see the message, then:

- We encrypt using the Public Key 🔐 and decrypt using the Private Key 🔑.

- The sender encrypts the message with the recipient’s public key 🔐.

- The recipient decrypts the message with their own private key 🔑.

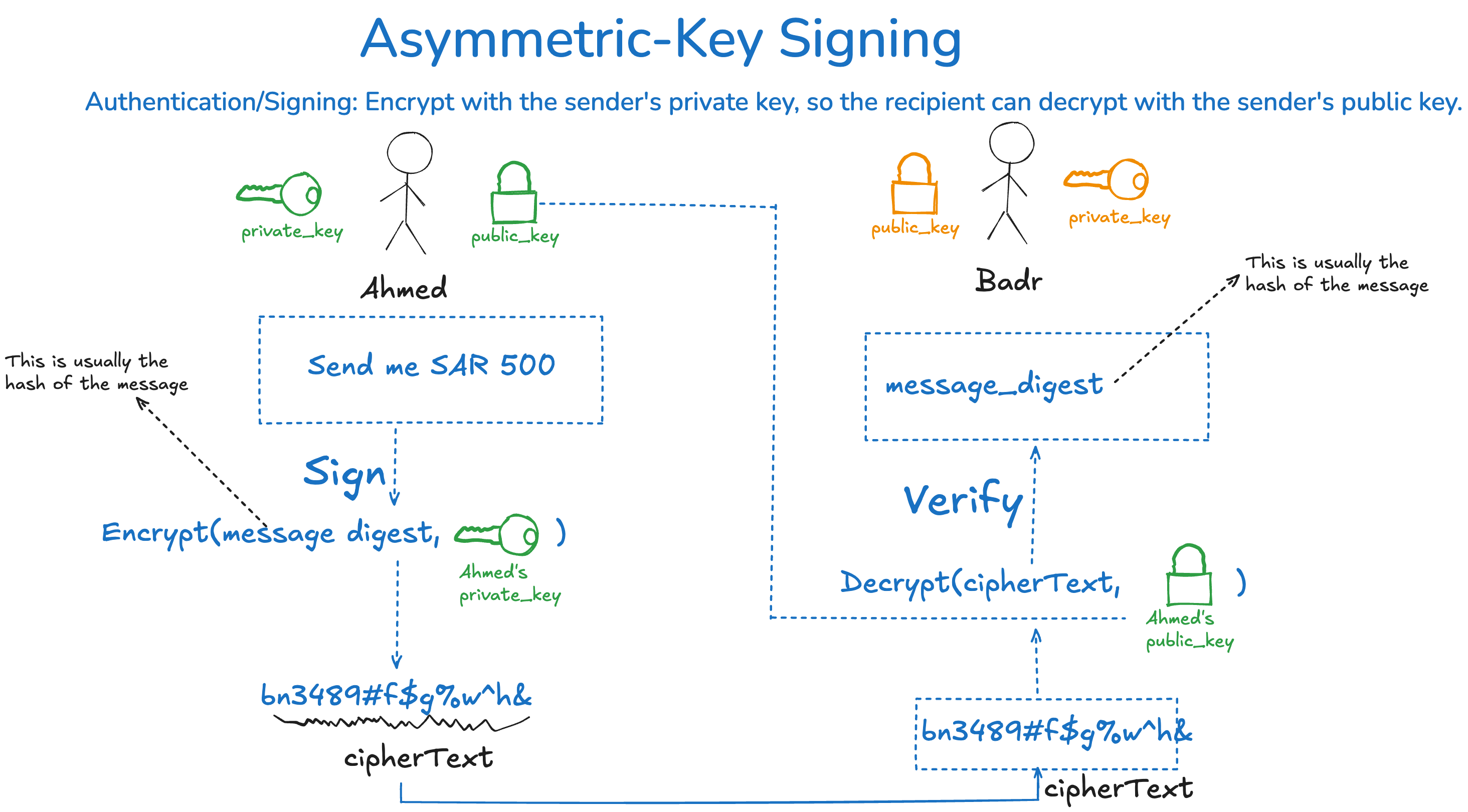

Asymmetric Algorithms for Digital Signature, Authentication, and Non-Repudiation

- If the goal is to proof the sender’s identity (authentication) while making sure that the sender can’t deny the message (non-repudiation), then:

- We encrypt using the Private Key 🔑 and decrypt using the Public Key 🔐.

- The sender encrypts the message with their own private key 🔑.

- The sender generates a message digest (a hash of the message) and then encrypts that hash using their own private key 🔑.

- This results in the digital signature.

- The sender generates a message digest (a hash of the message) and then encrypts that hash using their own private key 🔑.

- The recipient decrypts the message with the sender’s public key 🔐.

Common Asymmetric Encryption Algorithms

- RSA: Widely used for encryption, key exchange, and digital signatures.

- Elliptic Curve Cryptography (ECC): Strong security with much smaller keys.

- Diffie–Hellman (DH): Used to create a shared secret over an insecure channel without ever sending the secret itself. The ECC version (ECDH) is faster and more secure.

- ElGamal: Based on the DH problem. Supports encryption and digital signatures; used in systems like PGP.

- DSA / ECDSA: Used only for digital signatures. ECDSA is the modern elliptic-curve version.

- Ed25519: A fast, secure digital signature algorithm based on EdDSA and Curve25519. Strong, efficient, and widely used in SSH, TLS, and secure messaging.

Which is more secure, Symmetric or Asymmetric Encryption?

Oh no, Seriously!!😒 You asked the forbidden crypto question! Asking which is “more secure” is like asking whether a door or a window is more important when both are needed and serve different purposes! That’s why real-world systems use both.

A well-implemented symmetric algorithm (e.g., AES) can be extremely secure in one context, while a solid asymmetric algorithm (e.g., RSA with a larger key size) can be the right choice in another context. They’re simply designed for different purposes:

- Symmetric encryption is fast and great for protecting large amounts of data.

- Asymmetric encryption handles key exchange and identity verification (digital certificate).

Hashing

Hashing is a process that transforms any input (message, file, password, etc.) into a fixed-size string of characters, which is typically a sequence of numbers and letters. This output is called a hash value or digest.

- Deterministic: The same input always produces the same hash.

- One-way Function: It is computationally infeasible to reverse the process and recover the original input from the hash.

- Fast Computation: Hash functions are designed to be very fast.

- Data Integrity: Hashes help verify that data has not been changed. If the hash of a message matches the expected hash, the message is unchanged.

- Digital Signatures: Hashing is used in digital signatures to provide data integrity. The sender creates a hash of the message and signs it with their private key. The recipient can verify the signature and check the hash to ensure the message was not altered.

- Not for Authentication: Hashing alone cannot prove who created the hash or data.

- Hashing can’t provide user authentication because anyone can generate the same hash from the same input; there is no secret involved and no way to verify who created the hash.

- Hashing only proves data integrity, not identity.

- Avalanche Effect: A small change in the input produces a completely different hash.

- Collision: A collision occurs when two different inputs produce the same hash value.

- If an attacker can find two different messages with the same hash, they can substitute one for the other without detection. This undermines data integrity and can break digital signatures.

- Always use collision-resistant hash algorithms for security applications. Collisions make a hash function unsuitable for cryptographic use.

- MD5 and SHA-1 are vulnerable to collisions and should not be used for security purposes.

- Modern hash functions like SHA-256 and SHA-3 are designed to be collision-resistant.

Common Hashing Algorithms

- MD5: Produces a 128-bit hash. Fast but insecure and vulnerable to collisions.

- SHA-1: Produces a 160-bit hash. Not secure, deprecated, and not being used.

- SHA-256 / SHA-512 (SHA-2 family): Modern, secure, and widely used. SHA-256 produces a 256-bit hash; SHA-512 produces a 512-bit hash.

- SHA-3 family: The latest standard, designed to be secure against several attacks.

Example: SHA-256

echo "123456" | shasum -a 256

e150a1ec81e8e93e1eae2c3a77e66ec6dbd6a3b460f89c1d08aecf422ee401a0

What Hashing can do?

- Data Integrity: Hashes can verify that data has not been altered. If the hash of a message or a file matches the expected hash, the message or file is unchanged.

- Password Storage: Passwords are stored as hashes, not plain text. Even if the database is leaked, attackers can’t easily recover the original passwords.

- Digital Signatures: Hashes are used to create digital signatures, ensuring message authenticity and integrity.

- Checksums: Hashes are used to detect accidental changes in data (e.g., file downloads).

What Hashing can NOT do?

Encryption: Hashing does not encrypt data. It cannot be reversed to reveal the original input.

Confidentiality: Hashing does not hide information; it only verifies integrity.

Collision Resistance: Weak hash algorithms such as MD5 and SHA-1 can produce the same hash for different inputs (collisions), which is a security risk.

Authentication: Hashing alone cannot prove who created the data.

Protection from Rainbow Tables and Brute Force Attacks: Hashes, especially unsalted ones, are vulnerable to rainbow tables and brute force attacks.

- Attackers can use pre-computed tables to quickly reverse common hashes (such as commonly used passwords).

- To defend against this, always use a unique salt for each password and a strong hash function.

Diffie–Hellman Key Exchange

Diffie–Hellman (DH) is an asymmetric key-agreement protocol used to generate a symmetric cryptographic key.

- It allows two parties to securely establish a shared secret over an insecure channel without actually sharing the key.

- The resulting shared secret can then be used for symmetric encryption.

- ~Key Exchange~ Key Agreement protocol: DH lets two people agree on a secret key without ever sending the key itself.

- No Authentication: DH alone does not authenticate the parties. An attacker could perform a “man-in-the-middle” attack.

- How it works: Each party generates a private value and a public value. They exchange public values and use their private value to compute the shared secret.

- Use Cases: Used in protocols like TLS, SSH, and VPNs to establish session keys.

- Vulnerability: Diffie–Hellman is vulnerable to man-in-the-middle (MITM) attacks.

- An attacker can intercept and change the public values, form separate shared secrets, and forward messages so both parties think the connection is secure.

- DH alone does not provide authentication, so it is often combined with other mechanisms such as digital signatures or certificates to prevent MITM attacks.

Diffie-Hellman Key Exchange Interactive Demo

Message Authentication Code (MAC) & HMAC

Problem: Hashing alone is not enough in security

- Hashing provides integrity (i.e., we can tell if the data was modified)

- Hashing does not provide authentication.

- Hashing does not guarantee non-repudiation.

Message Authentication Code (MAC)

Message Authentication Code (MAC): Combine a message with a shared secret key to generate a digest.

hash(message, secret_key) = message_digest

- MAC: Generated using a secret key and a message. Only someone with the key can create or verify the MAC.

- MAC produces an output called message digest, which is a short piece of information used to authenticate a message and ensure its integrity.

- Message Digest: The resulting hash that verifies the message’s integrity and authenticity.

HMAC (Hash-based MAC): Uses a cryptographic hash function (e.g., SHA-256), combined with a secret key to produce the MAC.

- MAC is a broad term that doesn’t refer to any specific algorithm.

- HMAC is a specific, widely-used implementation of MAC that utilizes a secure hash function to ensure data integrity and authenticity.

- HMAC uses a strong hash function and is commonly used in modern cryptographic protocols.

- Purpose: Ensures that the message has not been altered in transit (integrity)) and that it comes from someone who knows the secret key (authenticity).

- Use Cases: Used in TLS, APIs, secure communications, IPSec, and OAuth.

⚠️ ⛔️💡Important Note: MAC/HMAC ensures integrity and authenticity but does not provide non-repudiation, which requires digital signatures based on asymmetric cryptography. Both the sender and receiver can deny the message since the shared secret key used in MACs can be known to both parties.

Digital Signature

Digital Signature: The sender creates the hash of the message and encrypts it with their own private key 🔑. The recipient then decrypts the signature using the sender’s public key 🔐 and compares the resulting hash to the hash of the received message. If the hashes match, the message is authentic and has not been tampered with.

How it works: The sender creates a hash of the message and encrypts it with their private key. The recipient decrypts the signature with the sender’s public key and compares the hash. If the hashes match, the message is verified as authentic and unaltered.

Integrity: Any change to the message will result in a different hash, causing the signature verification to fail.

Authentication: Only the sender’s public key can verify the signature, proving the sender’s identity.

Non-repudiation: The sender cannot deny sending the message, since only their private key could have created the signature.

Use Cases: Used in software distribution, legal documents, secure email, and protocols like TLS to ensure authenticity, integrity, and non-repudiation.

Examples of Digital Signature Algorithms

- DSA (Digital Signature Algorithm): DSA is a standard based on ElGamal signature scheme and used for digital signatures ONLY. It provides authentication and non-repudiation but not encryption.

- RSA (Rivest-Shamir-Adleman): RSA can be used for both encryption and digital signatures.

- ElGamal signature scheme: Based on the Diffie–Hellman problem, provides digital signatures and encryption.

- ECDSA (Elliptic Curve Digital Signature Algorithm): The elliptic curve version of DSA.

Note: Digital signature algorithms provide integrity, authentication, and non-repudiation, but they do not provide confidentiality unless combined with encryption.

MAC, HMAC, and Digital Signature Lecture White Board

Man-in-the-Middle (MITM) and Replay Attacks

MITM Attacks

Man-in-the-middle (MITM) attacks occur when an attacker intercepts and potentially modifies communications between two parties who believe they are communicating directly with each other.

Example of a MITM Attack

Ahmed wants to send “my bank account is SA123456789” to Badr over an insecure network such as the Internet. An attacker intercepts the message, changes it to “my bank account is SA9843976”, and forwards the modified message to Badr. Both Ahmed and Badr think they’re communicating securely, but the attacker has successfully manipulated their communication. As a result, when Badr sends money, it goes to the attacker’s account (SA9843976) instead of Ahmed’s real account (SA123456789), without either party knowing about the attack.

Protection Against MITM Attacks

- Digital Certificates and PKI: Use digital certificates from trusted Certificate Authorities (CAs) to verify the identity of the communicating parties.

- Certificate Pinning: Certificate pinning is a technique where a specific certificate or public key is ‘pinned’ to an application (e.g., WhatsApp) or browser (e.g., Chrome), allowing only the pinned/installed certificate to establish a secure connection with the server. It’s a common defense against man-in-the-middle attacks and unauthorized certificate usage.

Replay Attacks

Replay attacks are a form of network attack where an attacker intercepts and retransmits data that was previously exchanged between two parties.

Example of a Replay Attack

Ahmed sends “transfer SAR500” to Badr. An attacker may capture this message and resend it later, resulting in Badr receiving multiple unauthorized transfers of SAR500, even though Ahmed only intended a single transaction.

Protection Against Replay Attacks

- Timestamps: Include timestamps in messages so recipients can reject old messages.

- Nonces (Number used ONCE): Use unique, random numbers for each transaction that cannot be reused.

- Sequence Numbers: Include incrementing sequence numbers to detect duplicate or out-of-order messages.

- Challenge-Response: The recipient sends a challenge, and the sender must respond correctly using current information.

- Session Tokens: Use time-limited session tokens that expire after a certain period.

Certificate Authorities (CA) and Chain of Trust

A Certificate Authority (CA) is a trusted third party that issues digital certificates to verify the identity of entities (such as websites, organizations, or individuals) on the internet.

How Digital Certificates Work

- Digital Certificate: A digital document that contains a public key and information about the key owner, digitally signed by a trusted CA.

- Certificate Contents: Includes the subject’s name, public key, expiration date, and the CA’s digital signature.

- Verification: When you visit a website with HTTPS, your browser checks if the website’s certificate is signed by a trusted CA.

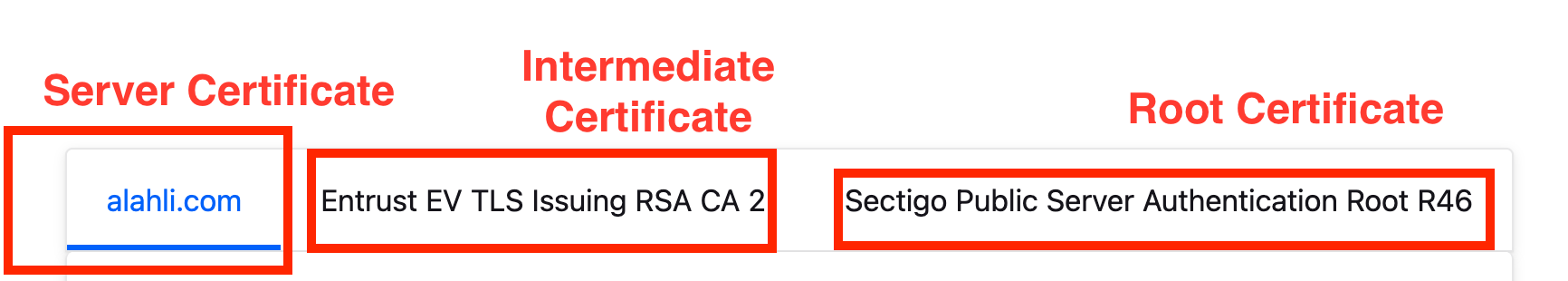

Chain of Trust

The Chain of Trust is a hierarchical system where trust flows from a root CA down through intermediate CAs to end-entity certificates.

- Root CA: The top-level authority that is inherently trusted by operating systems and browsers.

- Intermediate CA: CAs that are certified by root CAs and can issue certificates to end entities or other intermediate CAs.

- End-Entity Certificate: The final certificate issued to websites, applications, or users.

How Chain of Trust Works

- Root CAs are pre-installed in browsers and operating systems as trusted entities

- Root CAs sign certificates for Intermediate CAs

- Intermediate CAs can sign certificates for websites or other intermediate CAs

- When you visit a website, your browser verifies the entire chain back to a trusted root CA

Certificate Validation Process

When your browser connects to the bank website (e.g., https://alahli.com).

- Certificate Retrieval: The server presents its certificate and the certificate chain

- Chain Verification: Browser verifies each certificate in the chain is signed by the next level up

- Root Trust: Browser checks if the root CA is in its trusted store

- Validity Checks: Browser verifies the certificate hasn’t expired and matches the domain name

- Revocation Check: Browser may check if the certificate has been revoked

How CAs Prevents MITM Attacks

- Cryptographic Signatures: CAs use their private keys to sign certificates, which can only be verified with their public keys

- Trusted Third Party: CAs are vetted organizations that verify identity before issuing certificates

- Browser Protection: Browsers warn users if certificates are invalid, self-signed, or from untrusted CAs

- Hard to Forge: Attackers cannot easily create fake certificates that will be trusted by browsers

💡 Important: The security of the entire system depends on the trustworthiness of root CAs and their ability to protect their private keys.

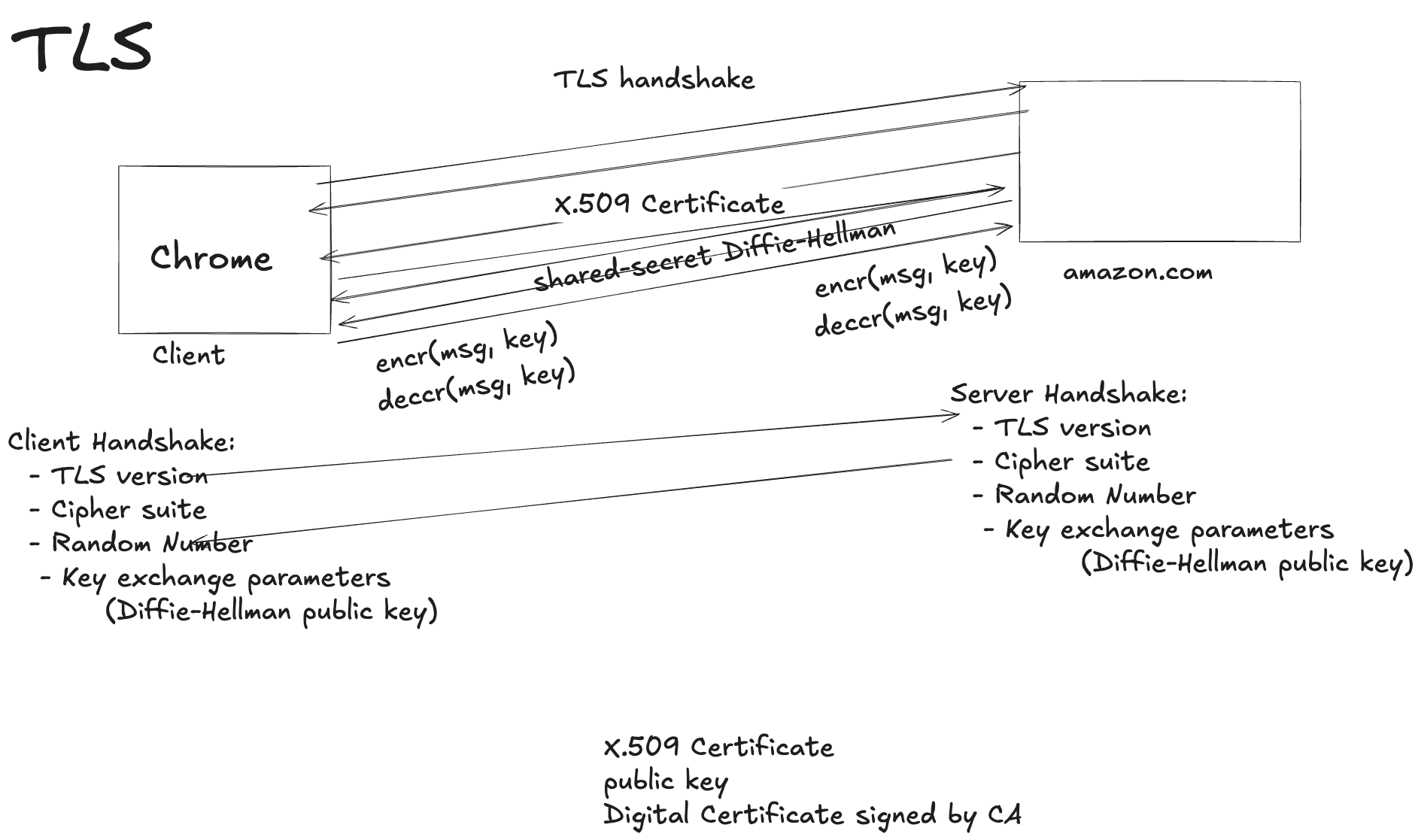

TLS (Transport Layer Security)

TLS is a protocol that secures communications over a computer network.

- It provides confidentiality, integrity, and authentication for data sent between clients and servers.

- TLS is built on the deprecated SSL (Secure Sockets Layer) protocol specifications.

- TLS uses asymmetric encryption for key exchange (often Diffie–Hellman), symmetric encryption for data transfer, and MAC/HMAC for integrity.

- TLS uses Digital Certificates to verify server and sometimes client identities.

- It’s composed of two layers: the TLS record and the TLS handshake protocols.

- Use Cases: Widely used in HTTPS, secure email, instant messaging, VoIP, VPNs, and many other secure protocols.